Kuandyk Ainabek

The Philosophy of Life and Business

| Предыдущая |

CHAPTER 8. DEVELOPMENT OF HOUSEHOLD AS CONSUMPTION ENTITY IN CONDITIONS OF SOCIAL ORIENTATION OF GLOBALIZATION

In the economic literature and course books, there are scarce research materials on the problems of household development. It is probably connected with the fact that the household does not take direct part in the market relations and production of the bulk of the national wealth.

The household is different from companies and the state. The difference lies in the fact that it is, first of all, a consumption entity, whereas companies are business entities rendering services and producing goods, which is the basis of the gross domestic product of the national economy. Furthermore, the household differs from the state because it does not take direct part in creation of the gross domestic product, does not have a legal form in participation in market and legal deals, unlike business entities.

The household appears to be an informal entity uniting people by kinship or other signs for living together in the same flat, house, stand-alone venue (hostel). Usually, this living together is characteristic of families by kinship signs or of two people of the opposite or of the same sex.

Living together is based on satisfaction of cultural, spiritual, emotional and physiological needs, reproduction of the kin, creation of an economic union for happy cohabitation in the form of the initial social unit.

In economic terms, some researchers consider the household as “a sector of employment, in which the members of the family or the interfamily kindred cover by their labour the personal needs of the family (kindred) in the form of natural products and services” [1, p. 210]. Thus, the household is opposed here to market employment and state mobilization employment [1, p. 210].

Further, the Russian official documents give a definition to the household, which is the total of persons living in the same housing unit or a part of it, both connected and not connected by kinship relations, jointly providing themselves with food and anything necessary for life, i.e. fully or partially combining and spending their funds. The household can consist of one person living on their own [2]. A similar definition of the household can be found in the methodological provisions on statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. They state that “the household is a group of people living together, combining (fully or partially) their income and property and jointly consuming certain kinds of goods and services, which mainly include housing and food. The household can consist of one person. The members of the household, as opposed to the family, may not have kinship relations” [3, p. 212].

The neoclassical thinkers sometimes share the viewpoint that the household should be identified with the personality of one person only. “Although the household consists of several persons – the husband, the wife, children, sometimes relatives and parents, having different needs, tastes and preferences, - the entire neoclassical theory identifies it with a single person,” writes J.K. Galbraith [4, p. 5].

“The household, thus identified with a single person, so distributes its income between different kinds of expenses that in the limit satisfaction received from each kind of costs, would be approximately equal. As it has been remarked, it is the optimal level of pleasure, i.e. the neoclassical consumption balance. Here emerges an obvious problem of the one, - emphasizes J.K. Galbraith, - whose means of satisfaction are leveled to the limit, whoever is meant – the husband, the wife, the children, taking into account their age, or the relatives living in the family, if any. But the traditional theory does not give any answer to it. Obviously, between the husband and the wife there is a compromise, which accords with a more idyllic concept of the lasting marriage. Each partner subjects their economic preferences to greater pleasures of family unity and marital bed” [4, p. 5]. With regards to it, B.G. Lipsey and P.O. Steineg remark: “In the theory of demand, we consider the household as our fundamental… unit, we should remark that a lot of interesting problems connected with the conflict in the family and parental control over the children’s fate fall out of the field of vision when we take the household as a basic decision-making unit. When economists speak about the consumer, they actually deal with a group of individuals forming the household” [5, p.71-71].

Furthermore, the American researchers M. Anderson, F. Bechhofer, J. Geshuny are approximately of the same viewpoint, writing: “At any moment of time only in a thousandth part of the household their members are trying to act as atomized individuals not taking one another into account – and such situations are internally unstable. Most households are continuously working out very complicated systems of rules for their members, establishing what behaviour is acceptable and what is not” [6, p.3].

In this matter, V.V. Radaev shares the above-mentioned authors’ viewpoint and emphasizes: “Usually the economist finds a traditional way out of the situation: he identifies the household as an integral unit with a single person making reasonable decisions (be reminded that the same has been done in the theory of firm). Therefore, the complicated internal structure of the household is taken out of consideration. In the meantime, in this structure a lot of serious problems are hidden, and one of them is connected with interrelations of genders in the household. The economist, as a rule, is indifferent to this problem. Initially, in the 20th century, the actions of the “homo economicus” were based on the combination of possessive and civil rights which belonged to the man. But in the 20th century the democratic equality of the man’s and the woman’s rights was established. And, at first sight, both of them started to equally claim for the role of the “homo economics”. Thus it became possible to again avoid raising awkward questions” [1, p. 214].

Therefore the representatives of this trend in the economic theory again demonstrate a superficial approach in research of quite a complicated social-economic phenomenon of the household. By the simplistic approach, it is easier to solve economic problems on paper, but there will be no advancement either in the theory or in solution of practical problems in developing the household and determining its role and meaning in increasing the efficiency of the national economy.

The household emerged after the breakup of the communal system based on division of public labour and dominion of private property, where the union of the opposite sexes and people connected by kinship could live together for ensuring their own well-being and continuation of the kin. This union was represented by the family which consisted of the parents, their own and adopted children, grandchildren, etc. In terms of economy, the household was formed also to reduce transactional costs and consumption costs, for effectiveness of the household budget, consumption spending. It should be reminded here that reduction of transactional costs also led to formation of firms as business entities, the market and the state.

At the early stage of the household formation and development, the household production took a leading place in support of the family life and creation of goods for the market. Therefore the dominance of the household production function for self-support and supply of goods for sale was characteristic of early stages of the household development. With regards to it, J.K. Galbraith wrote: “in pre-industrial communities women were valued together with their ability to give birth to children, for their efficiency in agricultural labour or home manufacture, and in the upper layers – for their intelligence, female attractiveness and other qualities which made it possible to properly welcome guests” [4, p. 3].

In the course of development of the public production, technology, market and national economy, the household production function has been reducing to the level of satisfaction of internal family needs, where the production of goods is acquiring occasional nature in megacities and cities. “Industrialization eliminated the need for the woman’s labour in such household occupations as spinning, weaving and making clothes. Combined with the technical progress, it considerably reduced the value of the female work in agriculture. In the meantime, the growing standards of national consumption, together with disappearance of personal servants – flunkies, resulted in an urgent need for people for management and other kinds of consumption service. Consequently, a new social virtue was given to running the household – well-thought-out purchase of goods, their preparation, usage and maintenance, as well ad care and attention to the housing and other property. A virtuous woman is now a very good housewife or, in a broader sense, a good housekeeper. Social life has to a greater extent become demonstration of virtuosity in performing these functions, a kind of a fair for demonstration of female virtues. The situation is still, - emphasizes J.K. Galbraith, - the same” [4, p. 3].

Further to the topic, V.V. Radaev writes, referring to the research work by G. Becker [7, p.32-63], that “in the meantime, the difference in the gender positions is especially obvious in division of the household functions, where the work is mainly the woman’s responsibility… Due to biological reasons, women are more involved in care after children and related household chores. And since women spend more time on them, they appear to have more reasons to make investments not in the market “human capital” but in the kinds of it which increase the efficiency of their labour in the household. Accordingly, in this situation, it is more reasonable for men to invest in the market “human capital” and receive higher remuneration in the market to maximize the joint “family” utility. Thus, there appears an endless circle in which biological differences are fixed and strengthened by economic actions” [1, p. 214-215]. This endless circle can be broken on the basis of the housewife’s labour evaluation and its registration at the state level, and also by using legal aspects, such as making agreements between the spouses, between the household and the state with regards to ensuring efficient public consumption and housekeeping.

If the households preserve the function of producing goods and services for the market, they turn into business entities and subjects of market relations. These entities perform the functions of cooperative production organizations, owner-operated farms. Therefore, it is necessary to single out the specifics of the household as the entity of benefits consumption and reproduction of the human kind unit, the human capital potential.

To discover the essence of the household, a connection should be established between the household production, labour, services, consumption costs, transactions, household budget, revenue and expenditure, extension and reproduction of the unit of the human capital potential.

Furthermore, external connections of the household should be separated from the internal relations, as the former are taken into account by business entities of the market sector and the state. The external relations of the household can include deals with business entities of the economic sector, market and state with regards to purchasing goods, consuming financial, transport and other services. The internal relations of the household are predetermined by the production and services on support of benefit consumption for reproduction of labour force and human capital.

It should be mentioned that research of the internal relations of the household represents cognition of the mini-economy of the national economic structure. And if the aggregate of the external and internal relations of the household is taken into account, it represents research of the micro-economy in the structure of the nation-wide economic system.

The foundation of the household existence is living together for opposition to external factors in the conditions of limited resources, continuation of kin and extension of human capital. It was predetermined by property relations on acquisition and alienation of benefits between the members of the household and the community and the conditions of insulation into an aggregate entity of consumption and reduction of transactional costs with regards to living together and extension of the human capital. Therefore, based on the above-mentioned, we can word the following definition of the household contents. It expresses social-economic connections in realization of essential relations of acquisition and alienation of benefits between the members of the household and the external environment in the conditions of limited resources, formation and development of the human capital and reproduction of the kin in the community, a stand-alone consumption entity, for reduction of transactional and consumption expenses, increasing the labour efficiency within this informal organization which functions on the basis of traditions and culture, predetermined by the conditions of the national economy development.

The following key functions are derived from the definition of the household: living together for reduction of transactional and consumption costs, increasing the labour efficiency within the household and opposition to external factors; reproduction of the kin and extension of the human capital; mutual enrichment of the spiritual, cultural, physiological and energetic potential of each member and the community as a whole.

“Consumption is a truly blessed thing according to the neoclassical model; it should be maximized by any honest and socially acceptable means. In addition, it is a supremely easy pleasure. The only thing one should think about is the choice of benefits and services. And their usage does not cause any problems. Both statements, - writes J.K. Galbraith, - are wrong. They overlook the circumstances to a great extent forming the image of the personal, family and social life. This very omission and the circumstances hiding behind it should be considered. These matters have essential consequences.

When possession of benefits and their consumption crosses a certain border, it becomes burdensome if the efforts connected with it can not be shifted to others. Thus, for instance, consumption of delicious and exotic dishes gives pleasure only when there is someone to cook them. Otherwise the time spent on cooking will soon bring to naught all the pleasure from the food for everyone but for geeks. More spacious and better-furnished housing requires more burdensome care and attention. It is the same with clothes, cars, lawns, sports equipment and other consumer luxuries. If there are people who can be made in charge of care and who, in their turn, can hire and manage work force necessary for the maintenance, then consumption is limitless. Otherwise consumption has strict limits. On seeing huge buildings erected in England in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, we immediately think about the wealth of their inhabitants. But most often it was modest, in terms of modern standards. It should be acknowledged that a more important role was played by the ability to shift administrative duties connected with consumption to the numerous and hardworking service class” [4, p. 2]. This service class included mainly women. With regards to it, J.K Galbraith sets the following example: “Transformation of women into the class of hidden servants was an economic achievement of paramount importance. Hired servants could be afforded only by a minor part of the population in the pre-industrial society; at our times, a wife-servant is available on the purely democratic basis almost for all male population. If this work was done by hired workers receiving monetary remuneration, they would become the largest category in the structure of the work force” [4, p. 2]. The cost of the housewives’ services is calculated, though these calculations are to a certain extent intuitive, approximately as one fourth of the gross domestic product [8]. This calculation and determination of the cost of the housewife’s services at the rates of the wage for equivalent jobs in the 70-s of the 20th century were made by the American researcher A. G. Scott, who fixed it at the rate of USD 257 a week and USD 13364 a year [8].

Measuring of the price of time in the household is the main problem for economists and society, to which the attention was paid by the Russian researcher V.V. Radaev, who noted the following: “There are immediate difficulties with measuring the time resource. First of all, it is due to the lack of the systematic data on the family budgets of time. But, which is the most essential, it is not clear how to measure the price of the time spent on the household, how to evaluate the product of labour which is initially not meant for sale. Two ways to overcome this major difficulty are suggested” [1, с.212]. These ways were proven in the research work by R. Growney. The first way is measuring the time spent on the household by opportunity costs, i.e. the amount of the salary this person would be able to gain for the given time in the labour market. The second way is based on the imputing to the fruits of the household the price which is set by the market for this kind of the product or service [9, p.296-297].

It would be appropriate to quote V.V. Radaev’s critical comments on the above-mentioned approaches of measuring costs of the households. He writes: “In the first case, the market price of labour is not always an adequate measuring instrument. For instance, productivity of labour in the household can be completely independent on the fact whether the housewife has a higher education diploma and a degree. And economists, after all, have to appeal to the difference of subjective evaluations, which representatives of more and less educated layers give to their housework. In the second case, someone else’s time spent by them in the labour market for rendering the service to you and your time spent in the household for self-service, notwithstanding the prerequisites of the economic theory, are more often than not measured by very different measures.

Do economic calculations influence the decisions of the housewife facing the choice: whether to buy a washing machine or not; whether to take the linen to the laundry or to wash it by hand? Yes, they do, and essentially. But it does not mean that “market” and house work are measured by the same equivalent. Firstly, these kinds of labour can be evaluated in different monetary units” [1, p.212-213]. This thought was borrowed from the American researcher V. Zelizer, who wrote: “in their daily routines people understand that… despite the anonymity of dollar banknotes, by no means all the dollars are equal or interchangeable” [10, p. 5, 36-70]. Further V.V. Radaev mentions: “Secondly, housework has not always been measured by money. More often than not it does not reach as far as to the quantitative evaluation, though the man does weigh the alternatives differing in quality. For instance, the mother is thinking whether she should go to work to have additional earnings or stay with her child giving him more care and attention. For her, it is not comparison of two monetary amounts.

The ranging the man does is nearly always the fruit of the “qualitative” decision. In other words, we can say “what is more beneficial” from the viewpoint of this very man, but we can not state “how much more beneficial”. Consequently, there appears a doubt in permissibility of mathematic operations and representation of behavioural characteristics in the form of smoothed curves. Certainly, the researcher may make calculations for the people he surveys, considering that they “allegedly” calculate monetary profits and costs of housework. But do not we replace, in this case, the main reasons with the secondary ones? And will not it be easier to admit that here the economic analysis faces the limits beyond which there are areas of measureless economy?” [1, p. 213]

It should be mentioned here that the criticism with regards to defining the monetary equivalent of the housewife’s services by the researcher R. Growney is necessary, as the salary for such services is predetermined by revenues of firms and various conditions of functioning of the market and the state. It shows the absence of the common value criterion for determining the services in the household sector. However, the statement by V.V. Radaev with regards to presentation of the household as an area of measureless economy, and refusal from the quantitative definition of the qualitative characteristics of phenomena in the space of the household based on the fact that it is really difficult and impossible proceeding from his subjective understanding of impossibility can not be the final verdict on the matter. It should not be forgotten that any qualitative characteristic in the economy has a quantitative measurement. Refusal from economic, quantitative analysis interconnected with the qualitative characteristic will not allow defining the household as a component of the economic system, finding out its place and vehicle of functioning and ways of revealing increase of efficiency in the organic integrity of the national economy.

Households, just like companies, the state, market, appear to be structural elements of the national economy. Therefore it becomes necessary to determine the vehicle of effective interconnection of the immediate, final consumption entity with companies, the market, state. This problem can be solved while determining the common criterion for monetary evaluation of services, labour in the household space.

The meaning of the household and female labour in it were especially noted by J.K Galbraith: “But for these services, all the forms of household consumption would be limited by the time necessary to cope with the consumption – to select, to carry, to prepare, to repair, to maintain, to clean, to service, to store, to preserve and to do all other tasks related to consumption of benefits. In the modern economy, the role of women in the matter of service has a crucial meaning for extension of consumption. The fact that this role has gained wide acknowledgement, but for separate objections which have appeared recently, is the formidable homage by the government to the convenient social virtue.

As it has just been just remarked, the women’s labour connected with facilitation of consumption is taken into account neither in the domestic income nor in the domestic product. This circumstance has a certain meaning for its disguise. Things which are not taken into account are often not noticed. At present, there has appeared an opinion that due to this reason and as a result of using traditional teaching methods there emerge conditions under which women, studying economic theory, do not realize their true role in economy. In its turn, it allows them too agree to this role with more readiness. If their functions in the economic sector were more clearly reflected in the modern teaching methods, it could bring about undesirable negative consequences” [4, p. 5].

The time has come to take the housewife’s labour into account, basing on the objective criterion conditioned by the result of the entire national economy. Such an indicator is the gross domestic product (GDP) or GDP per capita (Y), proceeding from which the price of one hour (t) can be calculated, both of free time and for the housewife’s labour invested. If the GDP per capita is denoted as Y, the price of the housewife’s labour costs per 24 hours (Тd) will be determined by the following formula: Тd=[Y:(D•t)] •t6, (10)

where D is the number of working days and days of paid annual leave a year – 306, without taking into account the days off and public holidays (59), t8 – the number of working hours a day – 8, t6 – the average number of hours of the labour invested by the housewife – 6 hours.

Thus, for instance, the GDP per capita in Kazakhstan was about USD 6 thousand in 2007; Тd=[USD 6000:(306•8)]•6=USD 14.71. Now let us take Тm to denote the uttermost price of the housewife’s labour costs per month; then Тm will be determined by the following formula:

Тm=Тd• D30 = USD 14.71•30 = USD 441.18 (11)

If the price of one hour of the housewife’s labour costs:

tr1=Y:(D•t8)=USD 6000:(306•8)=USD2.45 (12)

then the cost of one hour of free time (ts1) will be determined by the formula:

ts1= Y:(D•t16)= USD 6000:(306•16)=USD 1.23 (13)

Therefore, the annual uttermost payment of the housewife’s labour (t365) should be equal to: t365= tr1 • 365=USD 14.71•365=USD 5369.15. (14)

If we multiply this annual salary of the housewife by the number of households where this solution for remuneration is required, and they are about 50% of the total number, we will receive an impressive amount equal approximately to 10.2% of the GDP of Kazakhstan’s national economy for 2007. However, if we accurately calculate the costs for side and negative social and economic phenomena generated due to omission of the household from the field of vision and regulation by the state of the processes within this community, it can be understood that the above-mentioned expenses will be insignificant as compared to the losses in fight against drug addiction, prostitution, promotion of healthy lifestyle, building public nurseries, kindergartens, geriatric homes, boarding schools and service staff remuneration.

The state should be interested in remuneration of the housewife who brings up children and prepares the human capital for the labour market and state service, providing high-quality “social-economic product” necessary for strengthening the national security.

The full standard amount of the housewife’s remuneration should be derived from the economic conditions and the needs of the state, which is interested in considerable reduction of unemployment, extensive reproduction of the human capital, healthy lifestyle and increase of the community members’ cultural level to ensure its competitive ability. Another stimulus for housewives can be retirement insurance by the state, which will contribute to a significant increase in the number of children being born.

This idea of mine published in 2007 got continuation in Russia as soon as in 2009, in the proposals of V. Petrenko, the chair of the Federation Council Committee on Social Policy and Healthcare. She remarked that “If a woman will leave her three children at home and start planting a tree, there will be no use from it. We have made calculations by 18 regions of the RF so far. According to these calculations, the economy of funds in some regions turns out to be 4.7 times, if the mother will bring up three children at home and earn a salary for it. And she will also have pension deductions, and her service length will be taken into account ” [11].

For the research, households should be classified, subdivided into kinds and groups by important indicators. We propose the amended grouping by indicators and kinds of the household in Chart 4, initially borrowed from the Russian researchers.

This subdivision of households will allow regulating processes of this community development. It would be reasonable to subdivide households by key indicators: total income and income per household member; total number of people; housing, number of square meters per household member, etc.

Groupings of households make it possible to create models and vehicles of regulating social-economic processes in the community as a consumption entity.

Chart 4. Kinds of households by key indicators [12]

№ |

Name of key indicators |

Number of groups |

Conventional designation of indicators |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

by income per household member |

6 |

below the minimum of subsistence; on the level of the minimum of subsistence; above the minimum of subsistence; average subsistence standard; above average subsistence standard; high income |

2 |

by sources of subsistence |

15 |

salary at an enterprise, in an organization, institution of any form of ownership; income from entrepreneurship activity; income from farming enterprise; income from work for individual citizens; income from personal household plot; income from property; scholarship; old age or long service pension; disability pension; loss-of-breadwinner pension; unemployment allowance; various allowances (apart from unemployment allowance); another kind of social security; dependence on other persons; another source |

3 |

by belonging of housing |

2 |

state housing fund, |

4 |

by type of housing (for state and private housing funds) |

3 |

a separate flat; a shared flat (communal), a hostel, another housing, rented housing |

5 |

by availability (non-availability) of a land plot in use |

2

|

availability (non-availability) of a subsidiary plot, vegetable garden, garden, summer cottage or land plot |

6 |

by number of square metres of housing per member |

4 |

9; 12; 16; 20 and more |

7 |

by a certain number of the household members |

7 |

of 1 person, of 2 persons, 3 persons, 4 persons, 5 persons, 6 persons, 7 and more persons |

8 |

by age |

10 |

0.5-1 years, 1-3 years, 4-6 years, 7-10 years, 11-13 years, 14-16 years, 17-29 years, 30-39 years, 40-49 years, 50-54 years, 55-57 years, 58-62 years, 63 years of age and above |

9 |

by gender |

2 |

male, female |

10 |

by level of education |

7 |

higher, incomplete higher, secondary, vocational, secondary general, incomplete secondary, primary |

11. |

by nationality |

4 |

nationality, mixed nationality, national ethos, ethnic group |

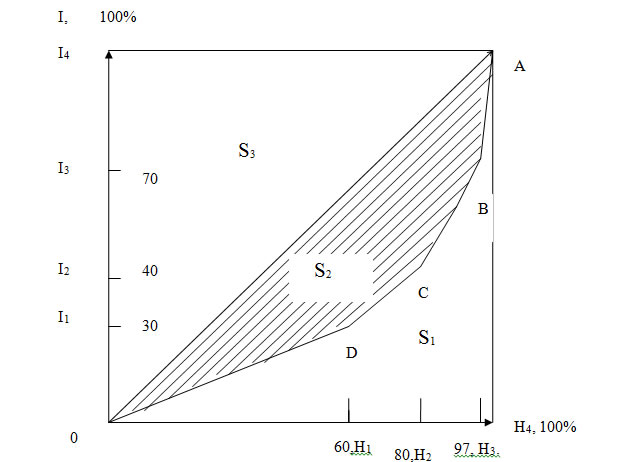

For instance, Figure 3 displays the model of determining inequality of household incomes, where the general view was borrowed from the famous American statistician and economist Max Lorenz [13, p. 102].

Whereas M. Lorenz’s graph on the horizontal line shows the percentage of the population group and on the vertical line – the percentage of income gained by these communities, our Figure 3 on the horizontal line displays the percentage of households, on the vertical – the percentage of income of household groups per member: I1- income at the level of the minimum of subsistence; I2 – above the minimum of subsistence; I3 – average subsistence standard; I4 – income of a high living standard.

In M. Lorentz’s graph, the straight of the bisecting line dividing the square into two halves is the line of the absolute equality, whereas the curve (ОDСВА) is the line of the actual inequality of income distribution. Now let us distinguish the areas of the square: S1, S2, S3. Area S2, hatched with oblique, “indicates the deviation from the absolute equality and, consequently, gives, - as P. Samuelson stresses, - us the measure of the inequality in the income distribution” [13, p.102]. By the correlation of S2 to S1+ S2, the income inequality indicator – G – is determined, named Gini

Figure 3. Model of determining extent of household income inequality

coefficient after the author of the formula; this approach is met in the course books by many authors [14, p.446 и др.]. Based on our Figure 50, this formula will have the following look: G = S2: (S1+ S2) = 0.442. (15)

This formula (15) is considered to be common in determining the indicator of the population income inequality in the economic literature. And the “Gini coefficient” indicator (G) points at the existence of the general inequality of household income distribution in Kazakhstan in 2005 equal to the value of 44.2%. This figure, upon the whole, allows determining inequality in population income distribution and comparing with various periods of the country’s development and with other states. However, it does not allow seeing inequality of income distribution between various groups of population, or households. For that, let us continue determining the inequality of Kazakhstan’s household income with the specific data for the year 2005 [15, p.13], where the basic indicator is the gross personal disposable income (Yh), which consists of the remuneration amount (L) and net mixed income and net profit (R), then:

Yh=L+R=2507682.mln tenge+3270442mln tenge=5778124.2mln tenge. (16)

Further, let us determine the total amount of the households received at the level of the minimum of subsistence, above the minimum of subsistence, average income level, high income level. Based on these data and gross personal disposable income, the shares of the households can be calculated, as well as the levels of inequality by each group with regards to the others, which is depicted on Figure 50. Thus, if the income of 4 groups of our example is compared, it is obvious that in group I4 the income is 20 times higher than in group I1 or I2 , and 5.7 times higher than in group I3. And the income of group I3 is 3.5 times higher than in group I1 or I2. These inequalities were observed among four groups of households in Kazakhstan in 2005. Such a big gap between the two last groups and the high-yielding group, 20 times, reveals existence of social injustice reasons, which will be a factor of social tension and increase of negative processes in the development of national economy and community. It should be mentioned that the gap, the inequality of population income between the lower and the higher groups of population should not be more, for the secure development of the country, than 10-fold, and for the socially oriented development of economy – 3-5-fold, as in highly developed countries: Sweden, Finland, etc.

Our calculation of the 20-fold gap in income between rich layers and 2/3 of the country’s population are confirmed by the following data: the share of the population with the income below the minimum of subsistence in the total number is 54.4%, and the share of the population with the income below the cost of the food basket in the total number is 10.8% [16, p. 69]. Summing up these indicators, we will find out that 62.5% of the population have lived in beggary at the time of the vigorous growth of the national economy in 2005. However, the official statistic data note that the gap was 6.8 times [16, p. 68].

Therefore, the problems of the household development should be regulated by the state on the basis of legal relations and economic approaches in ensuring healthy lifestyle of the population, extensive reproduction of the human capital and increasing efficiency of public consumption, considerable reduction of unemployment.

| Предыдущая |